"Dyson sphere? Boooring. Every type 1 baby species always comes up with the same idea, ‘hey lets just surround a star with mirrors and directly harvest the energy! What could possibly go wrong?’ Besides the fact your 80% of the way towards turning the star into a fucking bomb (don’t ask how we found that out), its basic ass vanilla shit.

Look, you don’t progress to a type three civilization by being uncreative hacks. Screw efficiency, the universe is our canvas and this is our art. No, we translocate entire water world planets and ice comets bigger than most moons using manufactured wormholes, hurl them into a designated star and use the steam produced to turn billions of giant turbines locked in orbit around the star. We then convert the mechanical energy to electromagnetic radiation pulses more powerful than neutron star pulsars and reflect them to nearby populated systems with mirrors. Take notes, monkeys."

How would you not move the turbine by hitting it with a jet of million-degree steam?

A type three civilization capable of generating wormholes and changing universal constants within a bubble of localized space light-years in diameter when a type 1er ask them how they do anything:

"Graviton stabilizers, tethers, oh and

Any other questions?"

What. Did. You. Do‽

“We did your mom, in every timeline and parallel universe where you were born too just to flex.”

Aren’t alternate timelines and parallel universes not the same thing?

I like to imagine there are infinite universes with slightly different starting conditions/cosmic constant values. Lots of them are non-starters for living observers because their fundimental forces didnt match up right to condense matter into stars after the big bang. Some universes like ours turn out to be goldilocks that balance the forces just right to for matter to assemble into structure and complexity.

Then for each particular universe theres an almost infinite amount of possible spacetime trajectories for matter to structure itself into from beginning big bang to ending heat death. Each unique possible state the universe could choose to become through probability as it progresses in time becomes its own branching divergent timeline, so like many worlds interpretation.

So no I don’t think they are the same thing. There are infinite universes with different seed values, and each one of them contains their own set of infinite possible timelines acting out all possible states that universe could experience given its constraints.

Now what about two separate universes with almost identical starting conditions that happen to share an almost identical timeline that leads to your birth? Are your near-copies the same you experiencing different universes, or just seperate clones?

I put together a thing for a Starfinder session where this one civilization needed a stupid amount of power in order to save their planet from a coming catastrophe. I based it on a laser propulsion method with black holes:

https://www.livescience.com/65005-black-hole-halo-drive-laser.html

In short, you shoot a laser at a black hole, and it whips around and picks up energy (blue shifting it). When it comes back at you, you get more energy than you put into the original beam (the extra coming from the black hole itself, of course). The original proposal was for propulsion, but you should be able to do it for power, as well.

I guess the only thing missing was making it heat up water to turn a turbine.

When writing the “turning the star into a fucking bomb” bit I was actually thinking about the black hole bomb same process as you describe but instead of extracting the energy or momentum it gets fed back into the system forming a runaway feedback loop leading to super nova level explosion. I doubted that a fellow science nerd on lemmy would see this comment and notice the slight error, but I could also see a real scenario where you completely cover a star with mirrors to the point its own energy is radiated back into itself forming a similar feedback loop causing it to explode.

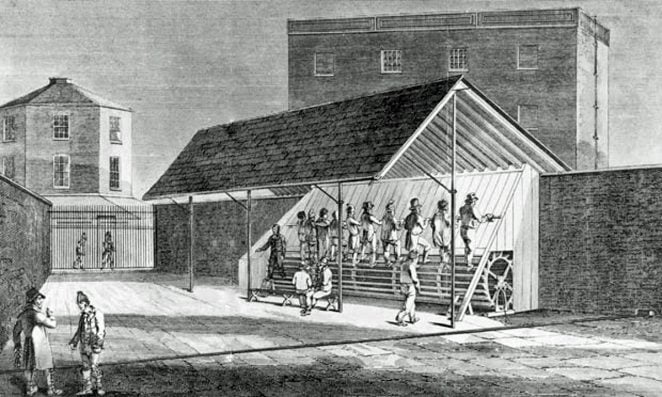

You can also use a variation on this effect to move star systems around. Surround a start with mirrors but instead focusing the light back to the star you make it focus it to a single point on the star. That single point becomes highly excited and erupts plasma at that location.

Because this is an extremely energetic plasma eruption and it’s only on one side you get movement in the opposite direction. The stars gravity field will pull the rest of the system with it.

You could only move it in the direction of the stars poles as unless you got really clever with timed pulsing (and I feel like that would be unreliable), you would vaporize any planets in the system.

I feel like the next big technological achievement will just be replacing water with some other fluid.

“Steam cycle? No, this is the much more advanced glycol cycle.”

The nice things about steam is you can get as much water as could want on earth, but something like ammonia which we used as a refrigerant for years would probably work well too and there’s planets with ammonia rich atmospheres.

The interesting thing is the cycles are fairly similar at a high level, you just run out in one direction for power and the opposite direction for cooling.

yeah but s t i n k y

That’s how you know you’ve got a leak. The reason they stopped using ammonia in the first refrigerators was because of they had a leak it would kill the entire household.

It’s why photovoltaics are so cool. Direct electricity generation without having to spin magnets in circles like neanderthals.

Solar is no doubt the coolest.

Hydro and wind are also very neat, going directly from mechanical to electric via generator, without a steam-turbine.There is also a very cool fusion-category based on dynamic magnetic fields, that basically form a magnetic piston which expands directly due to the release of charged particles via fusion and then captures the energy from that moving electric field by slowing it back down and initiating the next compression.

A fully electric virtual piston engine in some sense, driven my fusion explosions and capturing straight into electricity.

Feels so much more modern than going highly advanced superconducting billion K fusion-reactor to heat to steam to turbine.Yes! That is super cool tech. If I remember correctly, only about half of the fusion reaction energy was produced as charged particles though. The other half was free neutrons which are notorious for not interacting with the EM field.

I love the idea, it is such a cool direct energy capture method, but it is inherently inefficient.

I’d love to be proved wrong. I did a quick search and couldn’t find the company I’m thinking of, so I’m going off memory.

Kind of, it’s more complicated.

There are different fusion reactions, one example would be ²H-³He fusion used by Helion.

²H-³He is aneutronic, so doesn’t produce chargeless particles (every clump of stuff is either an electron or contains a proton). It is also an easy to achieve fusion reaction with good energy yield, with the downside that we don’t have ³He. Helion therefore has to split their fusion into two steps, producing ³He via ²H-²H fusion in a breeder-reactor and then fusing it in their energy-reactor. The first step would then emit neutrons and not really produce energy, the neutrons here could be used to further breed fuels.

Not having neutron emissions is quite useful because it allows you to make your fusion generator a lot smaller and safer around people, so it’s certainly something you want to avoid for far more valuable reasons than improving efficiency.If we get very good with fusion we could also use the much harder to achieve ¹H-¹¹B reaction, which produces some neutrons but at very low energy (0.1% of total energy output), and is effectively aneutronic for safety concerns (neutrons have low penetration power and don’t really activate material, so can’t be used to breed say weapons-grade fission material). ¹H and ¹¹B are common so require no further steps to produce them.

There might still be directly-to-electricity pinch-fusion approaches that use neutronic fusion, I tried looking for any but didn’t find an example. We’ll see what ends up being done in practice, but close to 100% energy utilization is at least possible using pinch-fusion.

On the other hand, the losses in heat-conversion are inevitably huge. The higher the temperature of the heated fluid compared to the environment the higher the efficiency, but given that our environment has like 300 K we can’t really escape losing significant amounts of our energy even if we use liquid metal (like general fusion) and manage to get up to 1000 K. The losses of going through heat are <environment temperature>/<internal temperature> (carnot efficiency), so would still amount to 30% energy loss if we manage to use 1000K liquid metal or supercritical steam to capture the fusion energy and drive a turbine. In practice supercritical steam turbines as used in nuclear plants hover around 50% efficiency at the high end.

The magnetic field in pinch-fusion interacts with the (charged) particles directly, which are emitted at (many many) millions of K. Therefore this theoretical efficiency will be at over 99.99%. In effect in heat-based fusion we loose a lot of that energy by mixing the extremely hot fusion results with the much colder working fluid.

They can’t control which particles fuse though. The Helion energy reactor still has the particles for deuterium to deuterium fusion. 50% of the time that gives your tritium+p and 50% is He3+n. I don’t know the preference of each fusion event in their reactor, but not all events will produce charged particles.

Fair point, though there are ways to change the probabilities of fusion paths, just not ever fully to 0.

Reaction probabilities scale with reactant concentration and temperature in ways we can exploit.

I tried to find some numbers on the relative probabilities and fusion chains, and ran into The helium bubble: Prospects for 3He-fuelled nuclear fusion (2021) which I hope is a credible source.This paper contains a figure, which gives numbers to the fusion preferences you mentioned.

Paraphrasing the paper in chapter “Technical feasibility of D-3He fusion” here, first we see that up to 2 billion K, the discrepancy between ²H-³He and ²H-²H fusion grows, up to about 10x. ²H-²H reactions will either produce a ¹n (neutron) and a ³He, or produce an ¹H and an ³H, with the ³H then (effectively) immediately undergoing the much more reactive ²H-³H producing a neutron too.

In addition to picking an ideal temperature (2GK), we can also further, for the price of less than a factor 2 increase of pressure, use a 10:90 mixture of ²H:³He, or even more. This will proportionally make the ²H-²H branch a factor 10/90 ≈ 11% as likely as the ²H-³He correcting for reaction crossection.

Past that, reactivity goes about with the square of pressure and the inverse of ²H concentration, so another 10x in fusion plasma pressure would net another 100x decrease in neutron emission at equal energy output.

Given how quickly fusion reactivity rises with better fusion devices, we can probably expect to work with much higher concentrations than 10:90 when the technology matures, but 10:90 at 2GK would still have about 1/100ᵗʰ the neutrons per reaction and less than 1/100ᵗʰ per energy produced compared to fully neutronic fusion like ²H-³H.The problem is solvable, but there is definitely a potential for taking shortcuts and performing ²H-³He with much higher neutron emissions.

Thank you for this researched, thought out answer. I really appreciate the time you put into it. Super interesting topic and I’m glad to learn more!

“Direct” (from energy created by a massive nuclear fusion reactor in space).

I mean to be fair, “add hydrogen to space, and wait” is a pretty simple reactor.

I don’t know why this is constantly criticized as a method of energy capture. Liquids allow for maximum surface area contact, creating more efficient heat transfer from the irradiated rods.

Armchair nuclear physicists should release an improved model before being so critical of the most effective and reliable method of energy generation we currently have.

I’d not that it’s criticized, it’s just kinda funny that everything comes back to steam engines

Oh for sure. It’s like a desire path or evolution’s crab in that way. I think I just misunderstood people’s criticisms as belittlement of the process without them understanding why it’s still the standard.

Fair enough, I’m sure people DO criticize it but it’s mostly a joke.

On a side note, are there any theoretical energy sources that DON’T involve steam? I’m not well-versed

Solar (photovoltaics), wind turbines, and hydroelectric are a few non-steam energy sources in use.

As for theoretical sources, some of the pulsed-power fusion concepts use the electromagnetic pulse from fusion to directly induce electrical power. But none of these have been demonstrated yet.

There’s also natural gas turbines

Excluding things that still involve moving fluid through a turbine or piston engine mechanically driving a dynamo or alternator while simply swapping out the steam for another fluid (too obvious), here’s all the ones I could find:

- batteries

- fuel cells

- photovoltaics

- piezoelectrics (which the other reply already mentioned)

- thermoelectrics (specifically, the Seebeck effect)

- photon-intermediate direct energy conversion (PIDEC)

- magnetohydrodynamic generators

Also not well versed, but last time I saw this topic come up, someone mentioned towers that wiggle in the wind and generate energy via the wiggles, apparently interacting with liquid at no point.

edit: Also maybe this YouTuber’s creation? https://youtu.be/BSxK5VagSb8

Yup. There are reed-like wind capture devices that generate piezoelectricity from compression. The same technology is being implemented in some nations to capture pressure energy on roadways and paths.

Steam engines are the crabs of power generation.

I don’t think it’s a criticism? It’s more about highlighting the slight absurdity of super-high tech power generation still using the same method that has been used since the very start of electricity generation. A turbine spun by evaporated water.

Hey now, sometimes it’s a turbine spun by falling water!

Easy there future man… One life-changing generation method per century

Behold…the future of green power. No steam or water needed at all!

Water has 1 to 14 expansion rate when vaporized. It’s always steam.

“wait a second, what is the steam made of?”

“Tin. Why, what do you guys use?”

“Erm, nothing, just, continue please.”

“Okay, so given the Strontium sulfide needed to balance the vapor out, we ended up with a Strontium-Tin mixture.We boys in the shop call it the Stin engine. Ain’t that a blast?”

"Nevermind "